June 10, 2017

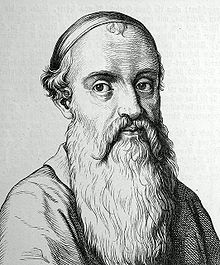

Devotions: Personalities of the Reformation: Hans Denck

Hans Denck was born in 1500 and died way too young in 1527 from the plague. It is surprising that more of the Reformers were not impacted by the plague – and possibly their families were impacted by this deadly disease. Anyway, even in his short life he was an influential leader in the Swiss and German Anabaptist movement. He was closely associated with Hans Hut (see below). At the age of 23 he was appointed rector in Nuremberg: he was nominated by Oecolampadius (May 26 devotion). Nuremberg was in conflict between the Lutherans, those disappointed with the fruits of the Reformation, and those leaving the Protestant movement and going back to the Catholic Church. Denck would be banned from the city in 1525 for his “conversations” that were overheard where he questioned infant baptism and the doctrine of Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and justification by faith. He was compelled by the magistracy of Nuremberg never to come within ten miles of the city for the rest of his life. He would end up in Augsburg. There he encountered a small group of Zwinglian’s whose members lived a life of strict morality and, eventually he would be bapitzed. Denck would become the leader of the Augsburg Anabaptist group. He would travel to Strasbourg in 1526, but this would make the Protestant Reformers like Capito (May 13 devotion) and Bucer (May 9 devotion) uneasy. He would then be expelled from Strasbourg in 1526 and soon arrived in Basel, Switzerland in 1527, sick in body, mind and spirit. He was tired of the conflict and constant persecution, and looked for some rest and peace in his life. He would write his friend Oecolampadius and ask for permission to meet. They talked often and Oecolampadius would write a pamphlet titled “Hans Denks Widerruf (Recantation). In this document Denck would outline his views on topics such as Scripture, free will, good works, baptism, and communion. His main thrust was that the person’s inner life with G-s is what matters most; everything outside is secondary if not useless. Denck writes:

“The inner Word is the ultimate Truth. This Word is Love, as God is Love. The Word was made incarnate in Christ Jesus. The quest to know and receive the Word is best satisfied through Jesus Christ. The true disciple of Christ must follow in his way, since this is the path of Christ Jesus, God’s Logos for this world. When we walk the way Christ walked, we are friends of God. For whoever supposes he belongs to Christ must walk the way Christ walked. Thus one enters the eternal dwelling of God” (The Spiritual Legacy of Hans Denck: Interpretation and Translation of Key Texts by Clarence Bauman, E.J. Brill, 1991)

(much of this devotion was adopted and adapted from gameo.com, Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia online, and Hans Denck: Reclaim the wisdom of Hans Denck, themennonite.org, The Mennonite online)

Hans Hut: Hans Hut was a bookbinder and a salesman. He traveled about Germany distributing pamphlets endorsing the Lutheran faith. For several years he was a visitor in Wittenberg. He would become unsatisfied with the Lutheran teaching of infant baptism and Justification by faith. He would refuse to have his infant child baptized, and was forced to leave his home and family and fled to Nuremberg where he met Hans Denck. Hut would leave to engage those participating in the Peasants War in Frankenhausen, Germany (Thuringia) – hoping to earn money selling his pamphlets and books. Here he heard the preaching of Thomas Muntzer and his message of the imminent coming of Christ.

I think it is interesting how many of the personalities of the Reformation, whether they were with Luther, or the Radical reformation, or even the Counter-Reformation, knew each other – were influenced by one another – and/or eventually openly sought the arrest of someone who once was their friend or colleague. This was a time of not only reformation, but complete change – and it was a matter of life or death.

Pastor Dave

Please collect two items of your choice for Trinity’s Table this week.