June 9, 2017

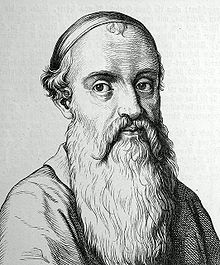

Devotions: Personalities of the Reformation: Menno Simons

“The error of the cursed sect of the Anabaptists … would doubtless be and remain extirpated, were it not that a former priest Menno Symons … has misled many simple and innocent people. To seize and apprehend this man we have offered a large sum of money, but until now with no success. Therefore we have entertained the thought of offering and promising pardon and mercy to a few who have been misled … if they would bring about the imprisonment of the said Menno Symons.” Thus read a letter that complained of Menno Simons, to the regent of the Netherlands in 1541.

Little is known about Menno’s early life. He was born in 1496 and died on January 31, 1561. He was ordained as a priest at age 28. Though educated in a monastic school and trained for ministry, he had never read the Scriptures. “I feared if I should read them they would mislead me,” he later wrote. “Behold! Such a stupid preacher was I for nearly two years.”

Menno Simons, like many, would have a crisis of faith which would be a seminal moment in his life. His crisis was over the Doctrine of Transubstantiationism. He could not conceive that the bread and wine he dispensed at each Mass did in fact change into Christ’s body and blood as Roman Catholic doctrine taught. He figured such thoughts had been suggested by the Devil, and prayed for God to ward them off. He would go on to write: “Finally, I got the idea to examine the New Testament diligently. I had not gone very far when I discovered that we were deceived, and my conscience, troubled on account of the aforementioned bread, was quickly relieved.”

Three years later he would hear about the beheading of an Anabaptist, sending Menno into another spiritual crisis. “It sounded very strange to me to hear of a second baptism,” he wrote. “I examined the Scriptures diligently and pondered them earnestly but could find no report of infant baptism.” Eventually, he was hit with a final crisis. Three hundred violent Anabaptists, dreaming of the imminent end of the world and attempting to escape persecution, captured a nearby town—and were savagely killed by the authorities. Among the dead was Peter Simons, Menno’s brother. “I saw that these zealous children, although in error, willingly gave their lives and their estates for their doctrine and faith … But I myself continued in my comfortable life and acknowledged abominations simply in order that I might enjoy comfort and escape the cross of Christ.” For nine months after his brother’s death he preached Anabaptist doctrine from his Catholic pulpit, until he finally left the church. A year later he cast his lot with the Radical Reformers.

Upon leaving the Catholic church he met a group of peaceful Anabaptists who strongly opposed Münsterite thinking. He joined them and was ordained. For the rest of his life, Menno and his family would live in constant fear of being labeled heretics. He traveled throughout the Netherlands and Germany, writing extensively and establishing a printing press to circulate Anabaptist teaching. He read the Bible literally, sometimes even legalistically; though he defended the doctrine of the Trinity in a small book, he refused to use the term because it did not appear in Scripture.

In one of his first writings, “The Blasphemy of Jan van Leyden” Menno opposed what he called the “proponents of the sword philosophy”: “It is forbidden to us to fight with physical weapons … This only would I learn of you whether you are baptized on the sword or on the Cross?” The Christian’s duty was to suffer, not fight, Menno believed. “If the Head had to suffer such torture, anguish, misery, and pain,” he asked, “how shall his servants, children, and members expect peace and freedom as to their flesh?”

In his later years, he was occupied with other internal Mennonite struggles, mainly over shunning excommunicated church members. But in each of his writings (more than 40 survive), he began by quoting Paul’s letter to the Corinthians: “No other foundation can any one lay than that which is laid, which is Jesus Christ.” He finally laid his pen down at age 66, as he became ill on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his renunciation of the Catholic church. The next day, he died a natural death. Today nearly 900,000 Mennonites follow his teachings. (much of this devotion was adopted and adapted from Menno Simons: Anabaptist peacemaker, christianitytoday.com)

The first Mennonite to arrive in Pennsylvania was Jan Lensen, arriving in October 1683. He came with 12 other German families who were Quaker weavers from Krefeld. They laid out the village of Germantown, north of Philadelphia. Following Jan Lensen’s arrival in 1683, at least 20 other Mennonite families settled in Germantown. They were from northern Germany and the Netherlands. In 1698 they chose papermaker William Rittenhouse as their first minister. Lancaster County is home to nearly thirty different Anabaptist groups in 412 congregations, totaling more than 52,000 members. Nationwide, there are 32 different Mennonite church groups in 2,422 congregations, totaling 252,993 members.

Pastor Dave

Please collect two items of your choice for Trinity’s Table this week.